Causes and symptoms of aortic insufficiency Diagnosis, degrees of aortic valve insufficiency Treatment Lifestyle with the defect Complications and prognosis

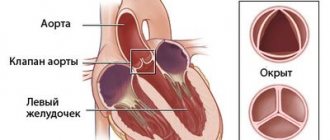

The aortic valve is a kind of connective tissue valve, consisting of three valves and located at the mouth of the largest blood vessel in the body - the aorta. Its function is reduced to delimiting the cavities of the left ventricle and the aorta. After blood is poured into the aorta from the ventricle, at the moment of its relaxation, the valve leaflets close tightly, promoting the movement of blood in the direction of the arteries of smaller caliber and preventing reverse blood flow into the cavity of the left ventricle. With a pathological change in the structure or mobility of the valves, their function is disrupted, which leads to the formation of aortic valve defects.

Such defects include stenosis and insufficiency of the aortic valve, and isolated aortic insufficiency occurs in only 4% of cases among heart defects.

Thus, aortic insufficiency is an acquired heart defect, characterized by incomplete closure of the valve leaflets at the time of diastole (relaxation) of the left ventricle, backflow of blood into it and a decrease in the volume of blood ejected into the aorta with a corresponding decrease in blood flow in the arteries and capillaries of all tissues of the body.

Chronic aortic insufficiency

Damage to the valve leaflets can lead to their non-closure, perforation and prolapse. The most common causes of chronic aortic insufficiency, caused by damage to the leaflets or root of the aorta, are listed in the table.

| Main causes of chronic aortic insufficiency | |

| Valve pathology | Pathology of the aortic root and ascending aorta |

| Rheumatism | Senile enlargement of the aortic root |

| Infective endocarditis | Aortoannular ectasia |

| Injury | Cystic medianecrosis of the aorta (as an independent disease and in Marfan syndrome) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | Arterial hypertension |

| Myxomatous degeneration | Aortitis (syphilitic, with giant cell arteritis) |

| Congenital aortic insufficiency | Reiter's syndrome |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Ankylosing spondylitis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Behçet's disease |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | Psoriatic arthritis |

| Aortoarteritis (Takayasu disease) | Osteogenesis imperfecta |

| Whipple's disease | Relapsing polychondritis |

| Crohn's disease | Ehlers-Danlos syndrome |

| Drug-induced valve damage | |

Another cause of chronic aortic insufficiency is wear and tear of the aortic valve bioprostheses.

Acute aortic insufficiency

Acute aortic regurgitation can also occur when the valve leaflets or aortic root are damaged. The causes of acute aortic insufficiency are less varied.

| Main causes of acute aortic insufficiency | |

| Valve pathology | Pathology of the aortic root and ascending aorta |

| Injury | Dissecting aortic aneurysm |

| Infective endocarditis | Paraprosthetic fistula and separation of the sewing ring |

| Acute prosthetic valve dysfunction | |

| Balloon valvuloplasty for aortic stenosis | |

Chronic aortic insufficiency

Aortic regurgitation results in a portion of the stroke volume being dumped back into the left ventricle. This leads to an increase in the end-diastolic volume of the left ventricle and, according to Laplace's law, tension in its wall. In response to this, eccentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle develops. While aortic insufficiency remains compensated, diastolic pressure in the left ventricle, despite the large end-diastolic volume, almost does not increase. Normal cardiac output is maintained by a sharp increase in stroke volume. However, myocardial fibrosis gradually reduces left ventricular compliance and decompensation occurs. Due to constant volume overload, the systolic function of the left ventricle decreases, the end-diastolic pressure in the left ventricle increases, its dilatation occurs, the ejection fraction decreases, and cardiac output decreases.

Acute aortic insufficiency

Acute aortic insufficiency quickly leads to hemodynamic disturbances, since the left ventricle does not have time to adapt to a sharp increase in end-diastolic volume. Effective stroke volume and cardiac output fall, leading to hypotension and cardiogenic shock. A sharp increase in diastolic pressure in the left ventricle leads to early closure of the mitral valve at the beginning of diastole, this prevents an increase in diastolic pressure in the pulmonary veins. However, further dilatation of the left ventricle increases and diastolic mitral regurgitation develops, leading to an increase in diastolic pressure in the pulmonary veins and congestion in the lungs. Compensatory tachycardia leads to shortening of diastole, resulting in a decrease in the period of diastolic filling and the opening time of the mitral valve.

Chronic aortic insufficiency

usually remains asymptomatic for a long time. After the development of left ventricular dysfunction, complaints appear caused by venous congestion in the pulmonary circulation: shortness of breath during exercise, orthopnea, nocturnal attacks of cardiac asthma. Dilatation of the left ventricle often leads to unpleasant sensations in the chest, which can intensify with extrasystole and in the supine position. Angina pectoris is not typical for aortic insufficiency, but is possible; in addition to damage to the coronary arteries, it is predisposed to a decrease in diastolic perfusion pressure in the coronary arteries, nocturnal bradycardia and a decrease in diastolic blood pressure, and severe left ventricular hypertrophy.

Acute aortic insufficiency.

Acute severe aortic insufficiency leads to a sharp disruption of hemodynamics, which is manifested by weakness, impaired consciousness, severe shortness of breath and fainting. Without treatment, shock quickly develops. If acute aortic insufficiency is accompanied by chest pain, it is necessary to exclude dissecting aortic aneurysm.

Why is the blood coming back?

Morphological metamorphoses (reduction in length, appearance of wrinkling, destruction of the structure due to calcification (deposition of calcium salts) in the valve tissue, deformation of the valves) lead to the valve losing its ability to close tightly and prevent the reverse flow of blood into the left atrium (valvular insufficiency with mitral regurgitation).

Often, along with changes in the valve itself, the tendinous chords and papillary muscles are shortened and deformed, that is, for mitral insufficiency not only cannot be excluded, but a possible combination with the pathology of the subvalvular apparatus should be taken into account.

The cause of mitral valve insufficiency in the vast majority of cases is rheumatic endocarditis, although sometimes another pathology can give rise to a new serious illness:

- Myocardial infarction;

- Cardiosclerosis;

- Injury;

- A heart tumor (myxoma) located in a specific location;

- Some of the congenital anomalies;

- Marfan syndrome;

- Diffuse connective tissue diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, systemic scleroderma).

The current situation creates unfavorable conditions for the functioning of the left ventricle, because a huge load falls on it, but the natural strength of the left ventricle for a long time helps it compensate for the blood flow in the systemic circle, so the patient continues to consider himself healthy for quite a long time.

Of course, the LV will not withstand this state of affairs indefinitely, therefore, after a certain period of time (it’s different for everyone), its contractility begins to fall, which is manifested by symptoms of congestion in the lungs. As a response to increased pressure in the pulmonary circulation (pulmonary hypertension), the mouth of the pulmonary artery (PA) is stretched and against this background, relative insufficiency of the pulmonary artery valve develops.

By the way, regarding the pulmonary valve. Predominantly, its insufficiency is relative and caused by the expansion of the mouth of the pulmonary artery.

In addition to pulmonary hypertension and everything that follows from it, hypertrophy of the right parts of the heart occurs, striving to ensure adequate blood flow. Gradually, the right ventricle hypertrophies, later expands (dilates), and a severe stage of decompensation begins for the systemic circulation.

Chronic aortic insufficiency

The most valuable information is provided by palpation of the pulse and auscultation of the heart. In addition, certain physical signs may indicate the cause of aortic regurgitation. In case of aortic insufficiency, be sure to look for signs of infective endocarditis, Marfan syndrome, dissecting aortic aneurysm and collagenosis.

Pulse

An increase in stroke volume in chronic aortic insufficiency leads to a sharp increase in blood pressure in systole, followed by a sharp drop in diastole. High pulse pressure is responsible for many physical signs of aortic insufficiency (see table).

| Physical signs of chronic aortic insufficiency | |

| Sign | Description |

| Galloping pulse (Corrigen's pulse) | Rapid rise and fall of the pulse wave |

| Musset's sign | Shaking your head to the beat of your heart |

| Ton Traube | "Cannon" tone over the femoral arteries in systole and diastole |

| Müller's sign | Systolic pulsation of the uvula |

| Durosier noise | Double murmur over the femoral artery: systolic with proximal compression, diastolic with distal compression and systole-diastolic with stronger pressure |

| Quincke's pulse | Pulsation of nail bed capillaries |

| Hill's sign | Blood pressure in the legs (phonendoscope in the popliteal fossa) exceeds blood pressure in the arms by more than 60 mm Hg. Art. |

| Becker's symptom | Visible pulsation of the fundus arteries |

In chronic aortic insufficiency, there may be a double pulse, characterized by two high systolic peaks. Signs of high cardiac output are not specific to aortic insufficiency; they are also possible in heart failure with high cardiac output due to sepsis, anemia, thyrotoxicosis, beriberi and arteriovenous fistulas.

Palpation of the heart area

In severe aortic insufficiency, the apical impulse is usually diffuse; it is palpated in the fifth intercostal space lateral to the midclavicular line, which is caused by dilatation of the left ventricle. It is possible to increase the strength and duration of the apical impulse. In addition, the apical impulse can be triple: waves are palpated due to the filling of the left ventricle in early diastole (corresponding to the Sh tone) and in atrial systole (corresponding to the IV sound and wave A of the jugular venous pulse). In the second intercostal space on the left, diastolic tremor may be palpated, in addition, systolic tremor is possible, due to the acceleration of antegrade blood flow through the aortic valve.

Auscultation

The main auscultatory signs are shown in the figure.

Auscultatory picture of aortic insufficiency. I, II, III - heart sounds; A2 - aortic component of the 2nd tone; P2 - pulmonary component of tone II.

Heart sounds.

The volume of the first sound may decrease with prolongation of the PQ interval, left ventricular systolic dysfunction and early closure of the mitral valve. The second sound may be quiet, there is no splitting (the pulmonary component is drowned out by diastolic murmur) or it becomes paradoxical. The third tone appears with severe left ventricular dysfunction. The IV sound occurs frequently; it is caused by the filling of the recalcitrant left ventricle during atrial systole.

Diastolic murmur.

The classic sign of aortic insufficiency is a blowing diastolic murmur that begins immediately after the aortic component of the second sound. It is best heard from above at the left edge of the sternum at maximum exhalation, when the patient sits slightly leaning forward. The severity of aortic regurgitation is better correlated with the duration of the murmur than with its loudness. At the onset of the disease, the noise is usually short. As it progresses, it becomes longer and longer and eventually occupies the entire diastole. With extremely severe aortic insufficiency, the murmur shortens again, which is due to the rapid equalization of pressures in the aorta and left ventricle due to an increase in end-diastolic pressure in the latter. In this case, the severity of aortic insufficiency can be assessed by other signs.

In severe aortic regurgitation, another diastolic murmur may appear at the apex. This is a Flint murmur, which appears in the middle of diastole or towards its end and is believed to be formed due to vibration of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve under the influence of a jet of aortic regurgitation or due to turbulent blood flow through the mitral valve slightly covered by this jet. Unlike the murmur of true mitral stenosis, Flint's murmur is not accompanied by a loud first sound and an opening click.

A brief mesosystolic murmur may be heard at the base of the heart and extend to the vessels of the neck. It occurs due to increased stroke volume and high blood flow through the aortic valve (relative aortic stenosis).

The change in the noise of aortic insufficiency during functional tests is described in the table.

| Influence of functional tests on the noise of aortic insufficiency | |

| The noise gets louder | The noise weakens |

| Static loads (for example, hand press) | Rising from a squatting position |

| Squatting | Valsalva maneuver |

| Administration of inotropes | Amyl nitrite inhalation |

Acute aortic insufficiency

Physical findings between acute and chronic aortic regurgitation vary greatly. In acute aortic insufficiency, signs of hemodynamic disturbances come to the fore: arterial hypotension, tachycardia, pallor, cyanosis, sweating, cold extremities and pulmonary congestion.

Palpation

Signs of high cardiac output characteristic of chronic aortic insufficiency are often absent. Pulse pressure may be normal or only slightly elevated. The size of the heart often remains within normal limits, the apex beat is not shifted to the left.

Heart sounds

The first sound is weakened due to early closure of the mitral valve. Pulmonary hypertension can be manifested by an increase in the pulmonary component of the second sound. III tone indicates decompensation.

Noises

Early diastolic murmur in acute aortic insufficiency is shorter and lower in timbre than in chronic aortic insufficiency. In severe acute aortic regurgitation, there may be no murmur as left ventricular diastolic pressure and aortic pressure equalize. The systolic murmur of accelerated blood flow through the aortic valve is sometimes present, but is usually quiet. Flint noise is usually short or not heard at all

Diagnosis of arterial insufficiency

First, an external examination of the patient is carried out, especially paying attention to the color of the skin of the limbs and around the lips, then the patient’s heart is listened to and an anamnesis is taken. To accurately diagnose arterial valve insufficiency, the following methods are used: - radiography (diagnosis of changes in the lungs); — electrocardiography (registration of heart biorhythms); - phonocardiography (determine the characteristics of systolic murmurs); — sounding (insertion of a catheter into the heart to take samples); — echocardiography (determine structural pathologies of the heart muscle); - ventriculography (helps to evaluate the structure of the cavities of the heart, its contractility, to identify various possible defects...).

ECG

In chronic aortic insufficiency, the ECG usually shows signs of left ventricular hypertrophy and enlargement of the left atrium, deviation of the electrical axis of the heart to the left. There are usually no conduction abnormalities, but they may appear with left ventricular dysfunction. Atrial and ventricular extrasystoles are often visible. Sustained supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia are rare, especially when left ventricular function is normal and in the absence of concomitant mitral valve disease.

In acute aortic insufficiency, the ECG may show only nonspecific changes in the ST segment and T wave.

Complications and prevention

The most important and dangerous complications of insufficiency are:

- decreased contractility and development of additional mitral valve insufficiency;

- disruption of blood flow through the arteries and, as a consequence, the possibility of death of a certain part of the heart;

- secondary inflammation of the inner membrane with the possibility of damage to the valves;

- separate contraction of individual sections of the atria.

As primary prevention, one should try to prevent diseases that are accompanied by damage to the valves; If the disease has already appeared, then effective treatment in the early stages can prevent deficiency. This also includes hardening, surgical removal of tonsils and filling of dental cavities, which can become a source of chronic infection.

If failure is already developed, then you need to move on to secondary methods of prevention, which are primarily aimed at preventing the progress of heart damage and failure of pumping functions. This is a conservative treatment that does not involve surgery, preventing relapses of rheumatism.

EchoCG

The cause of aortic insufficiency can be determined, the aortic root can be examined, and the size and function of the left ventricle can be assessed. Doppler ultrasound can detect aortic insufficiency and assess its severity. There are several ways to assess the severity of aortic regurgitation using color, pulsed and continuous wave Doppler studies.

2D mode and M-modal study

In two-dimensional mode, the cause of aortic insufficiency can be determined. With rheumatic damage to the aortic valve, the leaflets are thickened and wrinkled and, as a result, do not close. With infective endocarditis, compaction, wrinkling and perforation of the leaflets occur, and a threshing leaflet may appear; Infectious endocarditis should be suspected when vegetation is detected.

Aortic valve leaflet prolapse can occur in many conditions, including infective endocarditis, bicuspid aortic valve, myxomatous degeneration, and Marfan syndrome. Pathology of the aortic root is clearly visible along the parasternal long axis of the left ventricle. Aortic root dilatation is most often idiopathic, but other causes include Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, syphilis, and giant cell arteritis. With symmetrical dilation of the aortic root, the regurgitation jet is directed centrally, and with bulging of any one wall, it is directed eccentrically. To examine the ascending aorta, the ultrasound probe is moved one intercostal space higher relative to the parasternal long axis of the left ventricle. Sometimes transthoracic examination can reveal infectious endarteritis of the ascending aorta and its dissection. In severe acute aortic regurgitation, early closure of the mitral valve can be seen in the M-modal mode. In both acute and chronic aortic insufficiency, the regurgitant jet can hit the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve, causing its diastolic flutter. On two-dimensional examination, the anterior mitral valve leaflet may bulge toward the atrium in a dome-shaped manner, indicating moderate to severe aortic regurgitation.

Doppler study

Doppler ultrasound is used to detect aortic regurgitation and assess its severity. With a pulsed study, high-speed pan-diastolic blood flow is determined directly under the aortic valve. With a color Doppler study, you can see the source of the regurgitation jet, its size and direction. Constant-wave research gives an idea of the speed of the jet and its temporal characteristics. The depth of penetration of the regurgitant jet into the left ventricle on color Doppler examination does not correlate well with the severity of aortic insufficiency (as determined by aortography). To assess the severity of aortic insufficiency, a number of Doppler indices are used (see table).

| Echocardiographic assessment of the severity of aortic regurgitation | |

| Severe aortic regurgitation | Mild aortic regurgitation |

| The ratio of the maximum width of the aortic regurgitation jet to the diameter of the left ventricular outflow tract ≥ 60% | The ratio of the maximum width of the aortic regurgitation jet to the diameter of the left ventricular outflow tract ≤ 30% |

| The ratio of the cross-sectional area of the regurgitant jet to the cross-sectional area of the left ventricular outflow tract ≥60% | The ratio of the cross-sectional area of the regurgitant jet to the cross-sectional area of the left ventricular outflow tract ≤ 30% |

| Half-life of the diastolic pressure gradient between the aorta and the left ventricle ≤ 250 ms | Half-life of the diastolic pressure gradient between the aorta and the left ventricle ≥ 400 ms |

| Retrograde blood flow in the descending aorta, occupying the entire diastole | Slight retrograde blood flow in the aorta at the beginning of diastole |

| Dense spectrum of aortic regurgitation with continuous-wave Doppler study | Weak, ill-defined spectrum of aortic regurgitation on continuous-wave Doppler |

| Regurgitation fraction ≥ 55% | Regurgitation fraction ≤ 30% |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension ≥ 7.5 cm | Left ventricular end-diastolic size ≤ 6.0 cm |

| Regurgitation lumen width ≥ 0.30 cm2 | Regurgitation lumen width ≤ 0.10 cm2 |

| Restrictive type of transmitral blood flow | |

The ratio of the width of the aortic regurgitant jet to the diameter of the left ventricular outflow tract is measured along the parasternal long axis of the left ventricle, and the ratio of the cross-sectional area of the regurgitant jet to the cross-sectional area of the left ventricular outflow tract is measured along the parasternal short axis. Both of these indicators correlate well with the severity of aortic regurgitation on aortography. Another indicator is the half-life of the diastolic pressure gradient between the aorta and the left ventricle. The shorter the half-life, the more severe the aortic insufficiency, however, it is impossible to distinguish mild from moderate aortic insufficiency, and moderate from severe aortic insufficiency only by this indicator. The best indicators that correlate with aortography data are the volume of regurgitation and the regurgitation fraction. Regurgitant volume is the difference between the stroke volume of blood flow in the left ventricular outflow tract and the stroke volume of blood flow through the mitral valve (assuming there is no significant mitral regurgitation). The stroke volume of blood flow through the aortic valve is the sum of the effective stroke volume and the volume of regurgitation, and the stroke volume of blood flow through the mitral valve is the effective stroke volume. Regurgitation fraction is the ratio of the volume of regurgitation to the volume of systolic blood flow in the outflow tract of the left ventricle.

The equations for calculating these indicators are given below.

To assess the severity of aortic insufficiency, the proximal zone of regurgitation is also examined. It is used to calculate the area of the regurgitation lumen. An area of 0.3 cm2 or greater indicates severe aortic regurgitation. Using continuous wave Doppler, the presence of retrograde diastolic blood flow in the descending aorta is determined. Retrograde blood flow, occupying the entire diastole, indicates severe aortic insufficiency.

Transesophageal echocardiography

Transesophageal echocardiography is performed to exclude vegetation and abscess of the valve ring if infective endocarditis is suspected. In isolated aortic insufficiency, vegetations on the aortic valve are located on the ventricular side. In addition, transesophageal echocardiography is used to detect congenital aortic valve defects (eg, bicuspid aortic valve) and to exclude dissecting aortic aneurysm.

Stress EchoCG

Stress echocardiography is used to assess exercise tolerance. Unlike mitral regurgitation in aortic regurgitation, a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction during exercise does not allow a confident conclusion about hidden systolic dysfunction. The drop in ejection fraction during exercise in this case is due to a sharp increase in afterload and in itself does not serve as an indication for surgical treatment.

Etiology. Rheumatic fever. Infectious endocarditis. Syphilis. Atherosclerosis. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatoid arthritis. Prolapse. Injury.

Hemodynamic disorders. During diastole, blood flows back from the aorta to the left ventricle. If regurgitation is minor, no significant hemodynamic disturbances occur. With severe regurgitation, excessive filling of the left ventricle occurs with blood coming from the left atrium and an additional portion from the aorta. The volume load of the left ventricle leads to stretching of the muscle fibers. In accordance with the Frank-Starling law, the force of ventricular contractions increases, which, provided the myocardium is in good condition, leads to an increase in systolic output.

The left ventricle operates in hyperfunction mode, which leads to hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes with their subsequent degeneration. A short period of tonogenic dilatation of the left ventricle with an increase in the outflow tract is quickly replaced by a period of myogenic dilatation with an increase in the inflow tract. The left ventricular cavity expands, and relative mitral valve insufficiency forms. Left ventricular heart failure develops with hypertension of the pulmonary circulation. Due to resistance load, the right ventricle goes through the stages of hypertrophy with tonogenic dilatation, and then dystrophy of myogenic dilatation. Symptoms of right ventricular heart failure appear.

Mention should be made of the reflex expansion of peripheral arterioles due to massive irritation of the aortic and carotid zones of baroreceptors by a large volume of blood ejected by the left ventricle during systole. The reflex is biologically expedient; due to its existence, the end-diastolic pressure in the aorta decreases, and this contributes to an increase in systolic ejection.

Since the powerful left ventricle plays the main role in compensating for the defect, heart failure develops late in such patients. However, once it occurs, decompensation immediately becomes refractory to therapy due to the depletion of compensatory-adaptive mechanisms.

Clinic. At an outpatient appointment, a doctor may encounter the following types of complaints from patients with aortic insufficiency:

· feeling of pulsation in the head, in the vessels of the neck. This symptom complex is caused by sudden changes in blood pressure during one cardiac cycle;

· tinnitus, dizziness with a sudden change in body position, transient visual disturbances, less often cerebral syncope with a short-term fainting state. The listed symptoms occur with a significantly pronounced valvular defect with a large volume of regurgitation, which makes compensatory reflex reactions untenable, as a result of which the blood supply to the cerebral vessels during diastole becomes inadequate to the metabolic demand;

Cardialgia of various types. Pain in the heart area is often aching, pulling, and prolonged. They are explained by relative coronary insufficiency caused by inadequacy of blood flow to a large mass of hypertrophied myocardium;

· shortness of breath of varying severity, up to paroxysmal, tachycardia. These are symptoms of left ventricular heart failure. Our own experience shows that patients with aortic insufficiency rarely survive to develop biventricular heart failure.

Finally, in many patients with mild aortic valve insufficiency, complaints may be completely absent or limited to a feeling of pulsation in the vessels of the neck, head and heartbeat during physical exertion. These symptoms are characteristic not only of aortic insufficiency, but also of hyperkinetic cardiac syndrome in other diseases. They can occur in healthy detrained individuals and in athletes under submaximal loads. They are caused by massive irritation of the aortic and carotid reflex zones and adequate peripheral vasodilation.

On examination - moderate pallor, in the later stages combined with acrocyanosis. Musset's symptom - head shaking in time with the pulse, "carotid dance", pulsation of the pupils, pulsation of the uvula, pulsation of the vessels of the nail bed - Quincke's capillary pulse - are relatively specific for this defect.

The left ventricular impulse is visible to the eye, displaced in the 6th - 7th intercostal space. On palpation, it is strong, lifting, dome-shaped, its area increases to 6-8 cm2. The impulse is determined in the 6th - 7th intercostal spaces. Aortic pulsation is palpable behind the xiphoid process.

Percussion data. The characteristic aortic configuration of the heart with an emphasized “waist” (a “duck” or “boot” shaped heart). In the later stages - mitralization of the heart with a displacement of the upper border upward, right - to the right. Formation of the “bull heart”.

Auscultation. The first sound at the apex is quiet due to prolapse of the aortic valve composite. Weakening of the 2nd sound in the aorta for the same reason. A pathological 3rd sound is often heard at the apex of the heart due to stretching of the left ventricle at the beginning of diastole (“strike” of a large volume of blood).

Protodiastolic murmur in the aorta, in the Botkin area, at the apex of the heart is a classic regurgitation murmur of the decrescendo type, associated with the 1st sound. Typically, the noise is carried along the blood flow from the auscultation point of the aorta down and to the left. Functional diastolic Austin-Flint murmur is heard at the apex of the heart in the mesodiastole due to turbulence of blood flows from the aorta and from the left atrium or in presystole due to the relative narrowing of the left atrioventricular orifice by the mitral valve leaflet, which takes a horizontal position due to the high pressure on it from the blood flow from the aorta than from the left atrium. Misinterpretation of this murmur is a frequent source of overdiagnosis of mitral stenosis.

Systolic murmur in the aorta is associated with two reasons. The first is blood turbulence in the aorta due to its expansion. I. A. Kassirsky considered the second reason more significant. These are turbulences of blood around compacted short deformed valves. Systolic murmur in the aorta with “pure” aortic insufficiency is so constant that I. A. Kassirsky aptly designated it as accompanying.

A systolic murmur at the cardiac apex may originate from the aorta or be the murmur of relative mitral regurgitation.

The pulse is fast and high. Blood pressure - high systolic, low diastolic, high pulse. When auscultating the vessels, there is a double Traube sound, a double Vinogradov-Durosier murmur.

X-ray examination . In the dorsoventral and oblique projection there is bulging and lengthening of the arch of the left ventricle, rounding of the apex. Deep, high-amplitude pulsation of the left ventricle and aorta. The shadow of the aorta is expanded.

Electrocardiogram. Classic left ventricular hypertrophy syndrome: wave RV5.6, wave SV1.2, depression of the S interval - TV5.6; shift of the transition zone to the right; TV5.6 tooth is biphasic or more negative.

Phonocardiogram . Decreased amplitude of the 2nd sound at the aorta, 1st sound at the apex. 3rd tone at the top. Diastolic murmur in the aorta, in the Botkin zone, at the apex of the decreasing type, starting immediately after the 1st sound. The “accompanying” systolic murmur above the base of the heart occupies 1/3 - 1/2 of systole. It is low-amplitude and decreasing. At the apex there is a systolic murmur of relative mitral insufficiency associated with the 1st sound, and a diastolic, often presystolic (not increasing towards the 1st sound!) Austin-Flint murmur.

Echocardiogram. Increased size of the cavity of the left ventricle and ascending aorta.

Assessment of the degree of aortic insufficiency (N. M. Mukharlyamov et al.).

1st degree. Slight expansion of the border of the heart to the left (0.5 cm), increased apex impulse, pulsation of the carotid arteries. According to auscultatory-phonocardiographic data, there is a low-intensity protodiastolic murmur at the Botkin-Erb point, which is often determined only by auscultation (it may not be registered on the PCG). The ECG is normal, less often with signs of left ventricular hypertrophy in the corresponding leads. On the echocardiogram, the anteroposterior size of the left ventricle is normal or slightly increased (systolic up to 4.5 cm, diastolic up to 6 cm). Increased amplitude of contraction of the interventricular septum and the wall of the left ventricle.

2nd degree. Expansion of the border of the heart to the left and down (by 0.5 - 1.5 cm), increased pulsation of the heart, carotid arteries, “capillary pulse”. According to auscultatory-phonocardiographic data, there is a diastolic murmur, starting immediately after the 2nd tone and spreading throughout the entire diastole, of average intensity at the Botkin-Erb point and in the second intercostal space to the right of the sternum. The 2nd tone on the aorta can be moderately weakened. The ECG shows signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, often in the form of a combination of increased wave amplitude in the corresponding leads with changes in the final part of the ventricular complex. An echocardiogram shows an increase in the anteroposterior size of the left ventricle (systolic up to 5.5 cm, diastolic up to 7 cm). A marked increase in the amplitude of contraction of the interventricular septum and the wall of the left ventricle.

3rd degree. Significant expansion of the borders of the heart to the left and down (more than 2 cm); pronounced left ventricular impulse, “carotid dancing”, capillary pulsation and other characteristic symptoms of this defect. According to auscultatory-phonocardiographic data, there is an intense continuous diastolic murmur at all points of the heart, most pronounced in the aorta. 2nd tone is sharply weakened. The ECG shows signs of left ventricular hypertrophy in the form of a combination of increased amplitude of the R wave in the corresponding leads with changes in the final part of the ventricular complex. Echocardiographic signs of significant dilatation of the cavity of the left ventricle (an increase in the anteroposterior size in systole - more than 5.5 cm, in diastole by more than 7 cm), a pronounced increase in the amplitude of movement of the interventricular septum and the ventricular wall.

Aortic valve insufficiency is characterized by the appearance of oscillations of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve caused by blood regurtation. However, there is usually no correspondence between the severity of oscillation and the degree of aortic regurgitation.

Differential diagnosis. In case of pulmonary valve insufficiency, a protodiastolic murmur is heard at the base of the heart, however, unlike the murmur of aortic insufficiency, its epicenter is located in the 2nd - 3rd intercostal spaces to the left of the sternum. Other symptoms of pulmonary valve insufficiency help to make a correct diagnosis: right ventricular heart failure syndrome, epigastric pulsation, displacement of the right border of relative cardiac dullness to the right, electrocardiographic signs of right ventricular hypertrophy.

The diastolic murmur of relative pulmonary valve insufficiency (Graham-Still murmur) is soft in nature, of medium intensity, best heard in the 2nd - 3rd intercostal spaces to the left of the sternum, and is often accompanied by a systolic murmur of low and moderate intensity. Its most common cause is mitral stenosis with pulmonary hypertension. X-ray examination of such patients reveals dilatation of the pulmonary artery. In addition to mitral stenosis, the Graham-Still murmur can be heard in other diseases accompanied by hypertension of the pulmonary circulation: chronic nonspecific lung diseases, primary pulmonary emphysema, Aerza-Arrillaga disease, congenital heart defects. We observed a patient with a long-term history of tuberculosis, who, against the background of post-tuberculosis pneumosclerosis and emphysema, developed a picture of severe respiratory failure of a restrictive type, and right ventricular heart failure. Diastolic and systolic murmurs were heard at the base of the heart. The diastolic murmur was so intense that it served as a reason to rule out congenital heart defects. An autopsy revealed an aneurysmal dilatation of the pulmonary artery with relative insufficiency of the pulmonary valve. This confirmed the correctness of the intravital interpretation of the noise as Graham-Still noise.

Mitral stenosis with a protodiastolic murmur, starting from the opening click of the mitral valve, must be distinguished from aortic insufficiency with a protodiastolic murmur, the 3rd tone. Mitral stenosis occurs with signs of hypertrophy of the left atrium and right ventricle, aortic insufficiency is accompanied by left ventricular hypertrophy. Diagnostic difficulties are eliminated after a thorough analysis of the phonocardiogram and echocardiographic examination.

Hyperkinetic cardiac syndrome is characterized by a feeling of pulsation in the head and neck. It reveals a fast and high pulse and high pulse pressure. Systolic murmur from the base of the heart is carried out to the carotid arteries. However, there is no direct sign of aortic insufficiency - diastolic murmur on the aorta.

Etiological diagnosis.

Infective endocarditis occurs more often in middle-aged men. A history of rheumatic fever and heart surgery is not uncommon. Aortic insufficiency is accompanied by fever, which is relieved by large doses of antibiotics in combination with small and medium doses of glucocorticoids. Splenomegaly is common. With a long course of the disease - exhaustion, “drum fingers”, thromboembolism, infarction of the kidneys, brain, pulmonary embolism.

Tertiary syphilis occurs with damage to the ascending aorta and aortic valves. S.V. Shestakov, back in the 60s, drew attention to the uniqueness of the clinical symptoms of aortic insufficiency of syphilitic origin. This is the preservation of the second tone above the aorta due to increased vibration of its ascending section and the rarity of peripheral symptoms (fast pulse; “carotid dancing”) due to the destruction of the aortic reflex zone as a result of specific inflammation. Very characteristic X-ray data are dilation of the ascending aorta, signs of its aneurysm.

“Pure” aortic insufficiency of rheumatic origin is relatively rare. More often, as a result of rheumatic fever, a combined aortic defect is formed. One can think about aortic insufficiency in rheumatism if it is possible to identify direct signs of this disease - carditis, polyarthritis, combined mitral heart disease, laboratory markers of previous and (or) current streptococcal infection caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus.

Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease) and rheumatoid arthritis with visceritis have a fairly characteristic clinical picture. The detection of aortic insufficiency syndrome in such patients makes the etiological diagnosis reliable.

In systemic lupus erythematosus, aortic valve insufficiency is usually the outcome of Liebman-Sachs endocarditis. Less commonly, the defect is formed due to myxomatous degeneration of aortic tissue and thinning of the valve leaflets. One should think about the lupus genesis of aortic insufficiency if the clinical picture of the defect is revealed in a woman of childbearing age without a history of rheumatic fever and infective endocarditis, with “unmotivated” hyperthermia, benign polyserositis, nephropathy, a “butterfly” on the face, capillaritis, vasculitis, positive LE- phenomenon. Fever and visceritis are treated with large doses (60 - 80 mg/day) of glucocorticoids.

Atherosclerotic aortic insufficiency is diagnosed in elderly people, who, as a rule, have suffered from coronary artery disease and hypertension for a number of years. The second sound in the aorta in such patients is preserved and sometimes even enhanced due to its compaction.

In case of a traumatic defect, there must be a causative situation in the anamnesis (car accident, fall from a height). The defect is diagnosed based on a clear chronological connection between the injury and the appearance of diastolic murmur in the aorta.

Aortic valve prolapse can be combined with mitral valve prolapse, but can also be isolated in Marfan syndrome. The clinical picture of aortic insufficiency in a patient with a typical appearance characteristic of Marfan syndrome makes the diagnosis of aortic valve prolapse probable. To verify the diagnosis, echocardiography is necessary, revealing displacement of the leaflet during diastole towards the outflow tract of the left ventricle relative to a line drawn from the place of attachment of the aortic valve leaflets to the fibrous annulus of the aorta (K. I. Korytnikov, 1986).

We had to observe patient S, 53 years old, with a dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta, in whom, after an attack of severe precordial pain, a diastolic murmur appeared in the aorta. The patient's appearance, typical of Marfan syndrome, and the clinical picture of the disease made it possible to diagnose a rupture of the prolapsed aortic valve leaflets. At the section the diagnosis was confirmed.

Treatment. Conservative treatment is carried out according to the syndrome. For heart failure - glycosides, saluretics, peripheral vasodilators, nitrates. Indications for surgical treatment - aortic valve replacement with a ball prosthesis: left ventricular heart failure, cerebral syncope, ECG - left ventricular hypertrophy syndrome in combination with a decrease in diastolic pressure to 40 mm Hg. Art. and below.

Cardiac catheterization

All patients over 50 years of age with severe aortic insufficiency undergo coronary angiography before surgical treatment. In younger patients, the question of performing coronary angiography is decided individually, taking into account risk factors for atherosclerosis. Dilatation of the aortic root in aortic regurgitation may complicate coronary catheterization. In Marfan syndrome and aortic medianecrosis, the catheter must be manipulated very carefully so as not to damage the aortic wall. In addition to coronary angiography, aortography is performed to assess the severity of aortic regurgitation.

| Angiographic assessment of the severity of aortic regurgitation | ||

| Degree of deficiency | Left ventricular contrast | Contrast evacuation |

| Light (1+) | Weak, incomplete | Fast |

| Moderate (2+) | Weak but complete | Fast |

| Moderate (3+) | Intensity like aorta | Moderate |

| Heavy (4+) | Denser than the aorta | Slow |

Right heart catheterization may be necessary, for example, in cases of rapidly developing heart failure or a combination of aortic insufficiency and aortic stenosis.

In asymptomatic moderate aortic regurgitation, the prognosis in the absence of left ventricular dysfunction and dilatation is usually favorable. With an asymptomatic course and normal left ventricular function, aortic valve replacement is required in 4% of patients per year. Within 3 years after diagnosis, complaints appear in only 10% of patients, within 5 years - in 19%, within 7 years - in 25%. For mild to moderate aortic insufficiency, the ten-year survival rate is 85-95%. With moderate aortic insufficiency, the five-year survival rate with drug treatment is 75%, and the ten-year survival rate is 50%. After left ventricular dysfunction develops, complaints appear very quickly, within a year - in 25% of patients. Once complaints appear, the condition quickly worsens. Without surgical treatment, patients usually die within 4 years after the onset of angina and within 2 years after the development of heart failure. In severe clinically obvious aortic insufficiency, sudden death is possible. It is usually caused by ventricular arrhythmias resulting from left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction or myocardial ischemia.

Degrees of aortic valve insufficiency

The development of aortic valve insufficiency, like any other cardiac defect, occurs gradually, regardless of the etiology of the disease. Each of the pathogenetic stages is characterized by certain cardiohemodynamic changes, which is reflected in the patient’s health status. The division of aortic insufficiency according to degrees of severity is used by cardiologists, and to a greater extent by cardiac surgeons, in daily practice, since for each of the degrees the use of one or another volume of therapeutic measures is indicated. The classification is based on both clinical criteria and indicators of instrumental research techniques, and therefore, each patient with suspected or previously established diagnosis of “aortic valve insufficiency” must undergo a full range of clinical and instrumental examination.

According to the worldwide cardiological classification, aortic valve insufficiency is usually divided into four degrees.

The earliest, grade 1, aortic valve insufficiency is characterized by an asymptomatic course and full compensation of hemodynamic disorders. The only criterion for making a correct diagnosis at this stage of the disease is the detection of a small volume of blood (no more than 15%) regurgitating on the valve leaflets, which, on Doppler examination of the heart, appears as a “blue stream” extending no more than 5 mm from the aortic valve leaflets. Detection of grade 1 aortic valve insufficiency is not a basis for surgical correction of the defect.

Grade 2 aortic valve insufficiency, or the period of “hidden heart failure” is characterized by the appearance of nonspecific complaints that appear only after excessive physical activity. When recording electrocardiography in this category of patients, signs are noted that make it possible to suspect changes in the left ventricle of a hypertrophic nature. The volume of reverse blood flow during a Doppler study does not exceed 30%, and the length of the “blue blood flow” reaches 10 mm.

Stage 3 aortic valve insufficiency, or a period of advanced clinical symptoms, is characterized by a pronounced decrease in performance, the appearance of a typical anginal pain syndrome, and changes in blood pressure. An electrocardiographic study, in addition to signs of hypertrophic changes in the left ventricle, reveals criteria for ischemic myocardial damage. Echocardiographic criteria are the detection of a “blue flow” on the aortic valve with a length of more than 10 mm, which corresponds to a blood volume of up to 50%.

The fourth or terminal degree of aortic valve insufficiency is accompanied by pronounced hemodynamic disturbances in the form of the development of a powerful regurgitation flow, a volume exceeding 50%. At this stage, there is a pronounced dilatation of all cavity structures of the heart and the development of relative mitral regurgitation.

Chronic aortic insufficiency

Prevention of infective endocarditis

Once the diagnosis is made, patients must be explained the need to prevent infective endocarditis.

Drug treatment.

For chronic aortic insufficiency, vasodilators are used - hydralazine, ACE inhibitors and calcium antagonists. The main goal of treatment is to slow the progression of left ventricular dysfunction and stop its dilatation. Drug treatment does not eliminate the need to consult surgeons if complaints or left ventricular dysfunction occur. Recommendations from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association for drug treatment of chronic aortic regurgitation are shown in the table.

| Indications for treatment with vasodilators for chronic aortic insufficiency | |

| Indications | Strength of recommendation |

| Long-term medical treatment of severe aortic regurgitation with complaints or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, if surgery is not possible due to concomitant cardiac or non-cardiac pathology | I |

| Long-term drug treatment of asymptomatic severe aortic regurgitation with left ventricular dilatation with normal systolic function | I |

| Long-term drug treatment of asymptomatic aortic insufficiency of any severity with arterial hypertension | I |

| Long-term treatment of left ventricular systolic dysfunction that persists after aortic valve replacement with ACE inhibitors | I |

| Short-term drug treatment to improve hemodynamics in severe heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction before aortic valve replacement surgery | I |

| Long-term medical treatment of asymptomatic mild or moderate aortic regurgitation with normal left ventricular systolic function | III |

| Long-term medical treatment of asymptomatic aortic regurgitation with left ventricular systolic dysfunction if aortic valve replacement is indicated | III |

| Long-term medical treatment of aortic regurgitation with complaints and normal left ventricular function or mild to moderate systolic dysfunction if aortic valve replacement is indicated | III |

| I - strongly recommended, III - not shown | |

Vasodilators are absolutely necessary for patients with severe chronic aortic insufficiency and heart failure who for some reason cannot undergo surgery. In asymptomatic cases, continuous use of vasodilators is indicated for patients with severe aortic insufficiency, normal left ventricular systolic function and incipient dilatation of the left ventricle, as well as for any aortic insufficiency associated with arterial hypertension. In addition, vasodilators (usually IV) are used in preparation for surgery in patients with severe heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. In asymptomatic mild or moderate aortic regurgitation with normal left ventricular systolic function, vasodilators are not needed.

In the presence of complaints or systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle, the prescription of vasodilators is justified, but surgical treatment is indicated for these patients. After aortic valve replacement, vasodilators are needed only if left ventricular systolic dysfunction persists. There is no convincing data in favor of any specific drug. Some studies have shown that hydralazine improves left ventricular systolic function and reduces left ventricular volume. Nifedipine reduced left ventricular volume and increased ejection fraction in asymptomatic patients followed for a year. In a non-blinded, randomized study lasting 6 years, nifedipine compared with digoxin slowed the progression of left ventricular dysfunction and prolonged time to surgical treatment. Some studies suggest that ACE inhibitors reduce left ventricular volume. However, the benefit of ACE inhibitors was observed only if they significantly reduced blood pressure. Further research is needed to make more informed recommendations for the use of vasodilators in chronic aortic regurgitation. In practice, ACE inhibitors are most often used.

In cases of severe enlargement of the aortic root due to medial necrosis or other connective tissue pathology, beta-blockers are indicated. They help slow down the expansion of the aortic root. These data were obtained in patients with Marfan syndrome. In severe aortic insufficiency and aortic root diameter greater than 5 cm, replacement of the aortic valve and aortic root is indicated. For Marfan syndrome, surgery is indicated even if the diameter of the aortic root is smaller.

Treatment of the disease in children

When blood enters the aorta, the valve leaflets may close completely, causing some blood to flow back into the ventricle. He makes additional contractions to push it back out, but the blood returns again. The left ventricle is constantly experiencing additional stress and pressure from excess fluid. It gradually increases in volume.

Aortic valve insufficiency has 4 degrees. The first two usually do not require treatment; for the third and fourth, conservative (medicinal) or surgical treatment may be indicated.

Aortic valve insufficiency: conservative treatment

Drug treatment is aimed at alleviating severe symptoms in patients and preventing acute heart failure, which is one of the complications of aortic insufficiency.

It is indicated in the following cases:

- for long-term therapy of patients with severe aortic insufficiency, if for some reason they are not recommended for surgical treatment;

- for short-term effects to improve the hemodynamic condition of people who have pronounced symptoms of heart and aortic failure;

- for the treatment of patients in whom symptoms are asymptomatic, but studies confirm left ventricular enlargement;

- for long-term therapy of patients with severe symptoms and normal, mild or moderate degrees of ventricular dysfunction who are candidates for aortic valve transplantation.

Depending on how severe the aortic insufficiency is, a complex of medications is prescribed, combining the following groups of drugs:

- vasodilators (ACE inhibitors, hydralazine). They slow down the development of pathology. They are prescribed if there are contraindications to surgical treatment;

- cardiac glycosides with cardiotonic and antiarrhythmic effects;

- nitrates, beta blockers are indicated in cases where the aortic root is significantly dilated;

- antiplatelet agents are prescribed to patients with thromboembolic complications.

Medicines are recommended to be used to treat the disease, starting from the second stage.

The initial form of the disorder requires compliance with a special regime: patients are advised to limit vigorous physical activity and avoid nervous tension. It is necessary to be constantly monitored by a cardiologist.

Aortic insufficiency: features of surgical treatment

The most effective method of treating any heart defects is surgery. For aortic insufficiency, it is indicated for grades 2, 3 and 4 of the disease.

There are two main surgical techniques used:

- Prosthetics is the installation of a new valve that ensures the normal functioning of the heart. Artificial materials (silicone, metal) and biomaterials (donor valves or your own from the pulmonary artery) are used as prostheses. This type of surgical treatment is the most common and radical; after it, a long recovery period is required.

- Valvuloplasty is the elimination of valve defects (excision or suturing). The operation does not require opening the chest or general anesthesia. During surgery, a mechanical increase in the lumen in the area of the valve leaflets occurs. A special cylinder is used for this. This method is popular in the treatment of newborns.

The choice of material for a valve prosthesis depends on age. Bioprostheses made from tissues of pigs, cows or humans wear out within 10-15 years. After this period, the patient may need repeat surgery. A mechanical valve is installed for life, but the person must constantly take blood thinning medications (Warfarin, Coumadin).

The choice of valve must be agreed with the doctor, all necessary postoperative complications and a list of recommendations for recovery should be taken into account.

This form is manifested by complex pathologies: arterial hypotension, pulmonary edema. It quickly leads to complications in the functioning of the cardiovascular system.

Acute aortic insufficiency manifests itself with the following symptoms:

- weakness,

- severe shortness of breath,

- loss of consciousness.

Additionally diagnosed:

- bluishness or pallor of the skin,

- increased heart rate,

- a sharp drop in blood pressure.

Drug treatment is ineffective. It is used during preparation for surgery to stabilize the patient's condition. To reduce the load on the left ventricle and diastolic pressure, vasodilators are prescribed.

The prescription of additional drugs depends on the cause and degree of development of acute aortic insufficiency:

Treatment of aortic insufficiency directly depends on the symptoms and causes. If the initial diagnosis is carried out and the patient has no complaints, therapy is not prescribed. However, doctors strongly recommend visiting a cardiologist's office as often as possible. This is necessary to monitor a person’s condition and promptly prevent the disease. If heart failure is diagnosed, then treatment is carried out, which consists of taking medications.

As long as patients are diagnosed with grade 1 aortic valve disease and grade 2 aortic valve insufficiency, special cardiological and therapeutic treatment is not required. They just need to be constantly monitored by a cardiologist and have ECGs and ultrasounds done regularly.

There are no general methods for treating grade 3 and 4 aortic valve insufficiency. In order to determine the method of conservative therapy, it is first necessary to find out the cause of the defect and treat the disease that caused its appearance. And then begin treatment of aortic valve insufficiency.

Drug therapy in this case consists of prescribing cardiac glycosides; Isolanide, Strophanthin, Korglykon, Celanid. In addition, diuretins, vasodilators, and antianginal agents are used in the treatment of severe aortic valve insufficiency.

For patients with severe shortness of breath and persistent heart pain, surgical treatment is recommended, which consists of an operation to implant an artificial aortic valve.

Acute aortic insufficiency

The goal of drug treatment for acute aortic insufficiency is to stabilize hemodynamics before surgery. For cardiogenic shock, IV vasodilators are used; they reduce afterload on the left ventricle, reduce end-diastolic pressure in it and increase cardiac output. In severe cases, inotropic infusion is required. For aortic insufficiency caused by dissecting aortic aneurysm, beta-blockers can be used cautiously. They reduce the rate of increase in blood pressure in systole, which is very important in aortic dissection, but at the same time they reduce heart rate and thereby prolong diastole, which can increase aortic regurgitation and aggravate arterial hypotension.

In case of aortic insufficiency caused by dissecting aortic aneurysm or trauma, an urgent solution to the issue of surgical treatment is necessary. Drug treatment in this case is intended to increase effective cardiac output and slow down dissection.

In case of aortic insufficiency due to infective endocarditis, antimicrobial therapy is started immediately after blood is taken for culture.

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation is contraindicated for moderate and severe aortic insufficiency, as well as for dissecting aortic aneurysm. Aortic insufficiency also serves as a relative contraindication to balloon valvuloplasty for aortic stenosis, since after this intervention the insufficiency worsens.

Diagnostics

Aortic valve insufficiency can be suspected by examining the skin, presenting specific complaints and auscultation. Pallor is noted, and as the pathology becomes more severe, skin cyanosis occurs. When listening with a phonendoscope, a noise is detected on the right side of the sternum in the 2nd intercostal space, weakness of heart sounds, and sometimes arrhythmia. The pulse in aortic insufficiency is uneven and frequent. There is a large gap between diastolic and systolic blood pressure. Indirect signs indicating an acquired defect are:

- Musset - nodding the head in rhythm with the pulse;

- Landolfi - dilation of the pupils during the period of relaxation (diastole) and constriction during contraction (systole);

- Muller - pulsation of the soft palate along with the uvula.

Important! The patient has a “carotid dance”, which manifests itself in the form of a noticeable external pulsation of the carotid arteries, and Quincke’s capillary pulse, when the size of the colored field changes when pressing on the nail bed.

An accurate diagnosis is established after the following examinations:

- electrocardiogram;

- standard ECHO-cardiography;

- transesophageal echocardiography;

- duplex scanning and Doppler scanning;

- chest x-ray;

- general blood and urine tests;

- blood test for biochemistry;

- coagulogram analysis;

- phonocardiography;

- coronary angiography.

If necessary, tests for syphilis, blood culture for sterility, immunological studies, MRI, CT, insertion of a probe into the heart cavity and scintigraphy are prescribed.